KRAKOW

There’s a single tree that grows in the square opposite the Church of St Peter and Paul, up from a round hole cut through the granite pavers. If you stand at a certain position a few feet away and look back up at the church, that tree is the only evidence of nature amid all this cursed medieval development. Some of it’s branches are horizontal, almost like outstretched arms saying, “how did I get here?” or, “please accept my gratitude for leaving me put.” I shouldn’t be surprised, I know there are still gum trees in Sydney Harbour that were growing there the day the HMS Supply poked it’s wooden nose around South Head, but this tree here has heard more than it’s fair share of bombs and bullets and the general ravages of modern history….and survived. To think who these branches cast shade on! Soldiers, survivors and the doomed, royalty and peasants.

There are indiscernible symbols cut from a knife into the bark long ago that could be letters. Directly across under the church, statues of the 12 apostles throw flamboyant poses. As always, Peter has his set of keys that fit the lock of the gate to heaven but he’s twirling them on his finger. It’s like on school photo day when the photographer says, “Now lets take a fun one. Do something crazy!”

—————-

On my first night I throw my belongings in my bedroom, a second story creaky-floored high-ceilinged generous twin, with double door windows out onto the unkempt and lustrously leafy back yard, and rush to see the town. The room itself is part of private house that lies beyond the central precinct and I have to pass weedy vacant lots and crumbling graffitied buildings, and leg it through a long dark echoey tunnel under the highway to get to the streets with people on them.

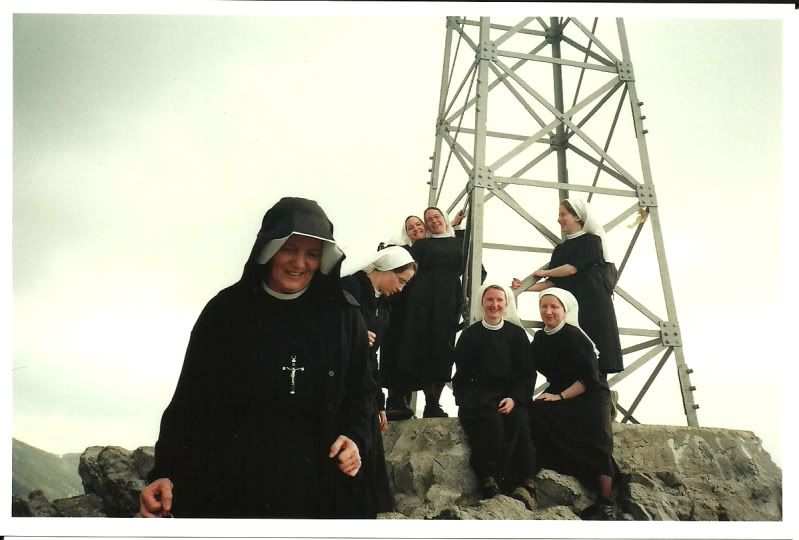

Music draws me to the door of a restaurant where an old man hunched over a piano is accompanied by a violinist with an eagle’s face, and they are involved in a sprightly gypsy waltz. It’s moody inside and each table has a lit candle casting quavering circles on red chequered cloths. My stomach says it will accept food as an excuse to investigate.

A beautiful waitress in traditional folk dress and with 18th century posture comes to take my order and I blush and say, as my finger scans down the menu list, “I’d like to try the Russian Borscht and a plate of assorted Pierogies please.” She neither smiles or answers, just writes it down and pads back to the kitchen in flat soled ballet shoes and I’m paranoid I’ve made a rotten tourist cliché decision. I notice then the violinist is glaring at me down his beak of a nose as he bows the strings, a protective warning. Maybe he is her father?

I sit and write in my diary and read my guide book to the flickering flame. There’s a glossary of simple phrases in the back and I try and say them by the accompanying phonetic examples. The food comes and even if it is a cliché there’s a reason for it. It’s the taste of centuries, the hopes, dreams and … of a whole country right there on a dinner plate.

When she comes back to brusquely clear the table I ask if she’ll help me with my pronunciations. She takes my book and holds it up to her face. “Na Strovia,” she says and mimes the action, “it means cheers for you.” My ears pick up that the piano player is now solo and I glance to see his partner is glowering at me with beady eyes, standing with his violin by his side.

——————–

I’m not qualified to sum up this place after only 3 days, but here are some general impressions:

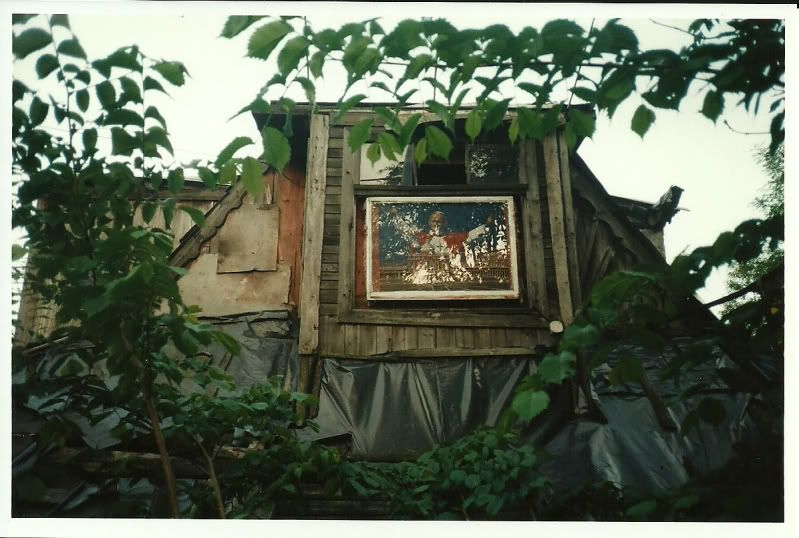

Every taxi ride within the city limits costs 7zloty ($2AU); Architecture students sit on the steps in the main square opposite the Cloth Hall and draw perfect straight lines freehand; drivers prefer not to stop at crossings and will park haphazardly on footpaths giving some streets the appearance of zombie holocaust film sets; on hot days some men pull their t-shirts up to rest below their chests to cool their bare round brown stomachs; There is a soup available in the Jewish quarter called ‘Yankiel the Innkeeper of Berdytchov’s Soup’; Pope John Paul 2, having been born and raised into priest and bishop-hood here, is the official mascot and his image is ubiquitous, even bakeries have pictures of him in their windows endorsing their bread; In the centre square there is an old woman who reads fortunes from a regular deck of cards in a cramped nook in the side of the garment hall, and at night when she’s gone she leaves her little cardboard box table there to mind her place.

———————–

The lady of the house is always flitting here and there in dark flowing Gothic gowns. She always has a smile and offers coffee whenever I’m loitering downstairs. She wears black nail polish and speaks scant English and will go fetch her son to translate if I ask a hard question. He’s the conductor of the orchestra – which costs as little as eight Australian dollars to see – for the Krakow Opera. His hair moves separate to his head in a plush wavy bounce.

“This house has been in our family for many years. It was a great meeting place for the bohemians of the town. My mother used to have parties here with Polanski and other artists… actors, singers. And the Pope John Paul has been here.”

“Really?” I’m impressed, “At the same time as Polanski?”

“No, of course not,” he answers dourly, “He was once the bishop of this area – before he was Pope – and it’s tradition for the bishop to visit each and every house on Christmas Day.”

“So this is quite a special house,” I say.

“It is a special house.”

————————-

ZAKOPANE

I’m going to climb the mountain today. The Sleeping Knight that watches over town. The lady at the hotel draws me a mud-map that’ll lead me to the trail head but I get lost just the same. I’m on a narrow leafy street on the outskirts, looking back and forth and a barking dog brings its owners to the front yard. They’re an old couple, probably in their 60s and the man is holding gardening secateurs and gloves in one hand. I show him the map and I try to explain where I’m heading, “the red trail…”

He points up the road and makes a curved hand gesture that I must go right and…. he stops talking, turns around and whispers something to his wife and she takes the dog inside and shuts the door abruptly. He opens the gate and gestures for me to follow. I expect that we’ll just get to the field at the end of his street and then he’ll point out my direction from there. When he gets to the gate he keeps on walking along the dirt road, through the field. I keep up with him, scrambling and tripping just behind. We come by a wooded area and he turns to me and says, “Op!” and points towards the forest and he climbs the bank off the road and walks into the trees.

This is getting really strange. We walk for 10 or so minutes and get deeper and deeper into the woods. It’s darker now as the sun can’t find it’s way through the canopy, and the only sound is our mulching footsteps on the soggy ground and a far off crow. This is the sinister forest of fairytales. We’re walking a few meters apart and there’s no point trying to talk. He’s still carrying the secateurs and gloves. My heart starts beating faster and it’s not from the brisk pace. Should I be following a stranger into the unknown like this? A little way off I see a structure with a high barbedwire fence around it and we seem to be walking towards it. I can hear a screeching noise and as we get closer I recognise it as the high whine of a bandsaw. I look up and see a surveillance camera above, attached to a tree. We step over some freshly cut logs and appear to be walking into someones compound. A thought flashes through my brain that I should turn around and run.

He turns just before the compound and we skirt the fence for some time longer. Suddenly I see light rays again and we’re at the far edge of the forest. He stops at the tree line and points across a shallow valley way off to a cluster of houses, a pencil line of smoke coming from a chimney. That is the head of the trail. He says something in Polish and I’m so happy I grab his free hand and shake it generously. He nods without expression, turns on his heel and heads back into the forest for the 20 minute walk back to his house, garden, wife and dog.

———————

After several hours of strained trudging up through pine forests of dead straight vertical lines, it opens up and the view is like nothing I’ve seen before. The eyes can’t take in all this visual data and depth and it all distorts at the edge of vision.

Muddy snow drifts putty the mountain creases, a ragged black bird of prey circles overheads like a halloween costume. Every so often I pass someone and exchange a breathless “Dzien dobry,” but no one stops to talk until I’m pulled up by a cheerful peculiar man in full fluoro climbing regalia, a professional mountaineering pole in each hand. I’d made the mistake of saying, “excuse me,” in English so he puts out one of his poles to block my path and exclaims, “whoa! you are a foreigner,” and asks me where I’m from.

“Australia.”

He says it again pushing his glasses up on his head, “but where are you from?” and as I repeat he cuts me off with, “I know this already! I know it from when you first speak! Where are you from, Sydney or Melbourne? I have visited both cities”

“Oh…” I really don’t want to get caught up here, “I’m from Gympie.” This means nothing to him so he just starts telling me of his Antipodean adventures and I have to wait for a breath to say, “Ok, really nice to meet you…but I’d better be off now,” and he looks piqued.

“Where are you going today?” he wants to know.

“To the top. To Giewont.”

He shakes his head and says, “Oh no, no, no. It is much too late in the day. You will not get there with the sun. You should turn now. You should walk back with me.”

“Sorry,” I said, more determined than ever, “I’ll try my luck.”

“Suit yourself!”

————————

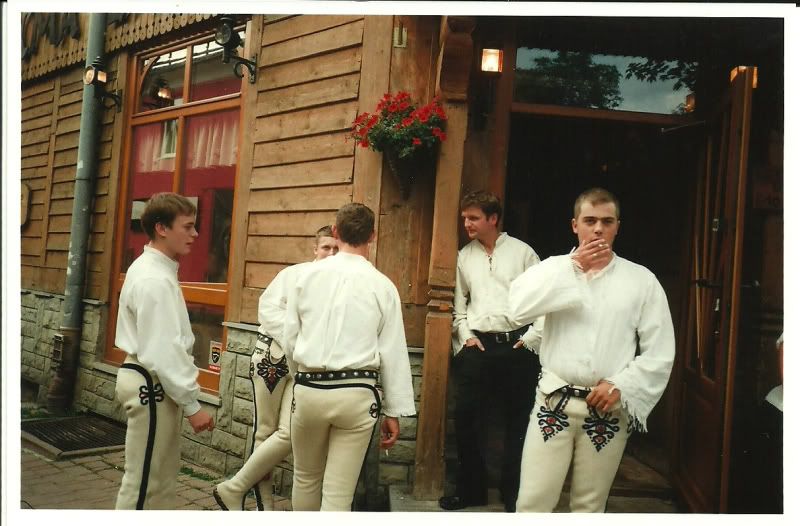

As I near the base of the final accent I can see patches of stark black and white against the rock-face like a giant chess board was smashed over the peak. As I get closer I find they are a group of nuns (what’s the collective noun?) hauling themselves to the top by the chains. They don’t seem to be moving. An older overweight nun has become stuck and the younger ones behind are laughing at her.

I reach the first post where the chain starts and I add my walking stick a growing pile that looks like an art installation. The path straight upward is a spiral of narrow ledges and one-way, there’s no turning back once begun. A foot wrong and you’ll have a date with sheer openness. A British man nudges his girlfriend gently upwards. She’s crying in fear of the height and drop and whimpering “I just can’t.”

I reach the top to find a cramped craggy crest where people look out and back to each other in shared accomplishment with glowing cheeks. Most are gazing up at the giant steel crucifix, that some crazy Highlander pilgrims lugged up here in 1901 in tribute to their God and master, or perch on it’s concrete base. The nuns are all chattering giddily and taking photos, girlishly hugging and holding hands, but suddenly, as if on some hidden cue, they take out Rosary Beads and all start a prayer round in unison. A quiet peaceful lull falls over the summit and it even feels like the air pressure just dropped. Us layhikers stop all talking and rustling of chip packets. We feel we’re a part of this holy moment too, even if we can’t understand their Polish devotions.

When they finish they take out sandwiches from their packs and scatter themselves around, still quietly under their meditation. I turn to ask one sitting near me where they have come from and she looks down and blushes bashfully and won’t answer.

I know all too late that I should’ve left before the nuns, but suddenly they’re up like a startled flock and heading for the chain path down the other side. It’s slow going and they’re all chortling gaily again but then a shriek from somewhere down below as they realise the chubby one is stuck again. This time its serious nun block. She’s wedged between two boulders and can’t stretch her short, thick leg down the drop to the next step. No one can reach her with her fellow sisters crowding the chain either side. The summit starts to fill up with people coming the other way. I ask if I can help but some Polish men are already on the case telling people to stand back so there’s nothing to do but wait.

It suddenly feels claustrophobic so I break the rules by scrambling back down the way we came up, praying I won’t meet traffic. Luckily when I do, the ledge is wide enough for me to press myself flat against the rock face to let them pass, frowning. I think about explaining but they’ll know soon enough.

I’m down and grab another wooden stick from the pile and hit the long trail back around down the east side of the range and home. I walk for a while and look back up the rocky peek far off and the splashes of black and white are still stuck on the side of the mountain.

—————————-

The next morning the pain in my legs isn’t apparent until I get out of bed. My leg muscles rebel when my feet hit the floor. The journey to the breakfast buffet is epic. Still, I’m determined to go back up. This time I’ll take the funicular up to Kasprowy Wierch and follow a path along another mountain range further into the Tartras and see where I end up from there. My free map has already ripped along the folded edges making neat jigsaw squares. The path undulates and curves along a rocky spine, I step aside to let a football team jog past in red jerseys.

Again the view is overpowering. To look directly south at the endless folds of mountains is to look straight into Slovakia. Far off I see the iron cross of Giewont, I could just pick it out of the rock and wear it on a chain round my neck.

I arrive at a cross roads, check my watch. It tells me it’s 4pm. I look at the sun and it’s very vague in what it says. It really feels like there should be a lot more hours left in the afternoon. I’m alone and the only sound is the air-conditioner whir of the pine forests way down below. I fit the squares of my map together.

There were only two other hikers behind me and I’ve notice they’ve turned back. I can’t see anyone else around. Up ahead coming down the steep path towards me is a single solitary figure. From a distance his thin hiking sticks make him look like a praying mantis. Before he gets to me he starts calling out.

“Turn around!” I think he’s saying.

He’s waving one of the sticks.

As he gets closer, “You’re going the wrong way. It’s too late. You must go back!”

Something sounds familiar.

“Hang on,” I recognise him as he gets closer, “I met you yesterday.”

“Oh. Crazy Australian!” he chides as he pauses to wipe his brow with a rag he takes from his pocket, “You can go up there but don’t take the blue path. Come back down this way.”

He waves a pole with a ‘pfft’ and keeps going.

When I reach the top it’s a 360 degree panoramic feast. Miles back down the slope I can see walkers draining back into the valley and the trail home. I find a patch of green grass and sit and just be. This is the first time in my life I can lay claim to having a mountain all to myself. It hits all of a sudden; a flood of emotions courses through me. I’m overwhelmed and am surprised by my own tears. I weep out of love for all people and am grateful for whatever events have led me to this top shelf of the world at this very moment, being able to look down at it and begin to get a sense of it all, a lofty perspective without leaving the ground. At my age, and not even having begun to learn anything about anything, but holding a knot of feelings in my chest. I weep for the love of a mother and father and sister and every soul I’ve encountered and called friend. I weep for the mighty mountain, who lets me scramble up its back and doesn’t shake me off like a dog would a bothersome flea.

But even a life affirming moment must be cut short if the fading day threatens to separate you from safety and a warm bed. With a last sweep around I pick myself up and brush the grass off my jeans and wonder about turning back, like my peculiar friend had urged. Well I didn’t heed his advice yesterday and that worked out just fine. I’ll take the blue trail.

————————-

There’s an antelope in the Tatra, only native to these mountains, that will graze on grasses disinterested in human presence and linger audaciously close if you happen to be sitting still and minding your business. But if you face her and try to approach she will back away, sounding a warning that’s akin to when the valve of a compressor is released, or the air-brakes on a semi-trailer.

——————–

The whole side of the hill is a steep wide sweep of shale and loose rock and I have to back my way down steadily, on hands and feet. The path is unclear and obscure painted arrows on larger fixed stones point me back on course a few times. My grip-worn Blundstone loses purchase and I slide a few feet before I reclaim my footing. If I slip and brake a leg I’ll be spending the night. There’ll be no more pilgrims on this path today.

The track, even when it became more solid, keeps pointing downwards for hours and hours and the upward incline seems like a distant memory. I wish for upward, if only for a couple of steps. My legs feel like houses of cards and threaten to topple at any moment. This is what I’ve learned about climbing mountains: going up is about the heart, going down is about the legs.

The path sinks into the woods. The nerves start to bite and the mind plays horror movies starring me and this forest; I startle at low hanging leaves brushing my forehead. The sound of a little bird picking through leaves nearby might be a rabid yeti. When I feel I can go no more I sit and the muscles lock tight and threaten to keep me in that position if I don’t move again soon.

You fool, you fool! Why don’t you ever listen? It’s all well and good to cry for all living souls on a mountaintop like some pretentious twit, but now you’ll die in it’s valley. You think you can square up against nature like it’s a sunday stroll? I hobble upright. Now it’s self-anger that’s the steam in my engine. Hours fall away and the sun is taken by the range above me and when I hear the sound of a far off car it might as well be Chopin. When I step off the track and back onto a bitumened street it is 11 o’clock at night.

KRAKOW (returned)

I go back to the tree to play my guitar and maybe earn some money. I just feel like singing, the money wasn’t really important, laying the guitar case out was just an act of commitment to the singing. That’s lucky though, as being in the middle of an affluent tourist area, people’s pockets aren’t exactly overflowing. Any busker will tell you it’s the poorer working class neighbourhoods where pennies are more likely to drop, in whichever city you’re in.

So standing there, under the perpendicular arms of the tree I belt out well-worn tunes I’d rote-learned as a voracious teen hungry to unlock their secrets so that I might have a go too: Paul Kelly, Slim Dusty, Go-Betweens, the Triffids. And now these my brain, written in and about my own homelands a hemisphere and a full day’s flight away, somehow peg me to the ground -in the mind at least- amid this years wanderings, and I remember who I am again.

“Cause that’s not her, it’s just the light. It’s only an image of her, just a trick of the light…”

A student strolls by and throws in some zloty and five minutes later an old alcoholic with wine-blushed cheeks asks me for money so I hand it straight out again.

Some rough looking kids are doing extreme BMX tricks in the square, mostly falling off and scaring pedestrians by peddling within an inch of them as they walk past. They eye me warily and occasionally ride right in front of me starring into my face, sizing me up. I’m just happy to sing to the apostles lined up in front of me, so try to ignore them. After an hour my voice gets tired and I’m running out of songs so I scoop up the fist of coins into my pocket and clip the case shut and walk off up the street amid the tourist current in search of coffee. I feel a tap on my shoulder, it’s two of the young bike riders from the square.

“You have a good voice,” one of them says carefully.

“Aw, Thanks,” I reply.

“We don’t have any money but we want to give you this,” he holds out his hand and drops a scrunched up silver foil into mine and closes my fingers around it.

Then his friend, who’s smiling broadly giving the thumbs-up and says, “It’s Polish, so it’s good shit!”

—————————

It’s nearing my last days and I decide I’ll go to the old fortune telling woman in the garment hall wall recess. The main problem here is that I don’t speak Polish. I ask a middle-aged man waiting on a bench to hear about his future if he speaks English. He says a little. I ask him if he’ll translate for me. He folds his newspaper and tucks it under his arm and looks at me gravely and says, “No. It is between you and she. If I tell the wrong thing it is very bad luck for you.”

————————-

It’s my birthday and I’m alone in an Eastern European city so I make a practical decision on how to spend it: I book a Communist tour. It’s been arranged through a telephone call to a tour company that I’ll be picked up at 2pm outside my lodgings. An old East German car putters up and the engine sounds like a mower. It only holds four people and the other two have cancelled so it’s just me and the young guide and it feels strange to sit quietly while he reels off his well-practiced tourist spiel. I feel like I need to make the reactions on behalf of all the missing people. I use “Wow” a lot.

“Welcome to crazy guides,” he started enthusiastically as he navigates the erratic traffic, “this tour is so crazy. Once even a wheel came off the car and bounced down the highway!”

I say, “Wow” again and raise both eyebrows but he reassures me and pats the dashboard, “Hey, don’t worry. We are very safe today.”

We drive out to the Communist designed post-war suburb of Nova Huta, a symbol of Soviet Union’s might and efficiency that was built to eclipse the quaint old-world Cracow. The first stop is an old Soviet milk bar, a place that hasn’t changed a single mirror tile or Stalin statue since 1950. Without being summoned a silent aproned waitress brings a tray of refreshments.

My guide throws a plastic folder of photos on the table. He is young, athletic and has a haircut to set your watch to. He starts off, “and now for some crazy facts,” and launches into stories of struggle and sadness, perseverance and victory.

Whilst mid sentence his mobile phone rings and he looks at it for a few seconds as if he’s never seen it do this before and then says, “excuse me, I must get this,” and walks over to the side of the room and takes the call. I just sip on my Coke through a wax straw and look at the photos. There’s one of Communist Propaganda on the construction site: a job for every man and woman! Three hands on one brick, placing it on a wall.

He comes back over and you can tell his mood has darkened slightly.

“Everything Ok?” I ask him.

“Yes, of course,” he says, and picks up the folder obviously trying to catch his train of thought, “let me see here…”

A flipping through pages. He looks forlorn and admits, “that was my ex-girlfriend,”

“Oh…,” I say, “One of those phone calls.”

“I will meet her at our old apartment today to go through our belongings. I just don’t know…,” he shakes his head and asks me earnestly, “do you think we can still be friends?”

I look at another black and white photo open in the tourist folder of a giant Stalin monument toppled by a cheering mob and I think that all the violent history of the world can seem like a nursery rhyme when played on the heartstrings.

“Hmm,” I thought out loud, “Well, you’ve come to the right place.”

“What do you mean?”

“Should we skip that church and go and get a beer?”

—————————

The colossal Nowa Huta steelworks was built to resemble a mighty castle from the front and placed thusly so the sun could rise from directly behind it each morning and the workers travelling towards it by foot or tram could be blinded by the majesty of their lives.

—————————–

The beer has made him a new man.

“We still have some time left. I want to show you something,” he says to me.

We’re back in the car and circumnavigating the steel works on unkempt potholed roads. He turns into a back lane that skirts the high chain-link barbed wired fence, stops the car and gets out.

“It is against the rules but I would like you to drive the Trabant now,” he says.

I don’t need convincing. Once in the drivers seat I test the pedals and reef it into gear and bunny-hop into forward motion.

“Now you can change into two because one is for start,” he instructs, “A lot of gas now… and three…go, go!”

We’re flying along now and the overgrown bushes are whipping the shell.

He starts relaying facts about the car, yelling over the straining engine.

“This one is a 600cc 2 stroke engine, and the body is basically plastic.” He thumps his fist on the roof, “Can you hear that?”

“This is cool!” I shout back, “What’s the fastest you’ve taken it?”

“About 100 kilometers an hour…but with a good wind,” and we’re both laughing, but mainly from the glee of speed.

Around a bend the deadend catches me by surprise and he barks and reaches over and pulls down hard on the steering wheel, “Slow, slow, slow, slow!” and we nearly end up crashing into some old wooden packing sheds but the brakes are good and the turning circle even better.

“Shit, that was close,” he says grinning, “Ok, let’s go again.”

Taking local-knowledge back streets we avoid the afternoon traffic and we’re nearing the city again where he will drop me off.

“What do you think of Polish people?” he wants to know.

“Honestly, I don’t want to generalise. I’ve only met a handful of you,” I say, “but I get a good feeling from being here.”

“Some of my customers have said we don’t smile much. You must understand, we are an optimistic people. But to have lived between two superpowers for centuries it is impossible not to get crushed.” he explains and pulls into a vacant space, “We are still learning how to smile.”

———————————

I’d been copying down names from gig posters around town that look interesting. One that caught my eye had a colourful lo-fi aesthetic and I wrote its details in my notebook: ‘Rachel Orette.’ A google search bore no fruit and I was about to give up on that one but as I stared at the scrawl on my notepad my crossword brain deciphered the mistake. The poster was two-lined when the words should be joined, and the confusingly ornate ‘R’ is actually a ‘B.’ – It’s Bachelorette! A great band from NZ, we played together at a festival outside Wellington years ago so maybe they’d remember me? It’s my last night.

I walk into the club and Annabel, the creative heart and singer of Bachelorette (she’s playing alone tonight), does indeed recognise me and I join her entourage at a table where she implores me to sing a few songs before she starts, and after some drinks I think it might be okay. It’s downstairs in a cramped basement bar and people have wedged themselves in every available space, all smoking and adding their share of body heat to the rising temperature.

For a solo performer Annabel is travelling with a lot of gear, the stage is cluttered with laptops, instruments and effects pedals. She loans me her guitar and I get three songs out and people are polite considering they have no idea who I am.

“Dziekuje, Krakow,” I banter with the audience, “I’ve had a great time here, you’ve been good hosts. Plus it’s my birthday today, and it’s nice to spend it with you.”

A cheer goes up and when I leave the stage and squeeze into a space by the bar the barmaid puts a shot of vodka in front of me and says Happy Birthday. I thank her and to my surprise she has one ready for herself just under the counter and we shoot together.

Some of the punters nod at me as they pass en route to the bathroom, some even shake my hand. Annabel steps up onto the stage where she and her various machines burst into an electro-pop aural opulence. She has a projector that beams morphing patterned hypnotic synchronised images onto a screen behind her and her floating vocal melodies are just as entrancing. I notice the shotglass in front of me has somehow filled itself and the barmaid is there miming a down-the-hatch. Again it’s in unison. This one is harsher on the throat and I grit my teeth whereas the kick sends her face into a dimpled smile. “You must try this one too,” she yells above the music with a devilish grin, “It has honey.” We cheers and down-the-hatch.

People are trying to dance on the sides of the room and I get pushed back away from the bar in the crush. The music, and the potency of the local hospitality, is sending signals to my brain and feet too but there’s no room move. Annabel is making a song out of a disco beat. What a great and unexpected way to end my days here. This time tomorrow I’ll be in Berlin, a full days speeding train ride away. That reminds me, I still have to pay my board, pack and be up before dawn. Should probably leave soon. I feel a finger poke me in the ribs. I turn around and it’s the cheeky barmaid and she has a shot of vodka for me in her hand, and one for herself in the other.

———————

I have two seats to myself and stare out at unkempt fields beneath a sprinkling of lite European rain and when we go through a tunnel it’s suddenly my own reflection. I’m mortified to remember stumbling home last night and singing at top note. I was getting off on the reverb in the tunnel. Dear God, I even sung the Australian National Anthem. I never thought I’d be one of those travellers, heady with pride for their own country and not shy of letting everyone know. My brain was poisoned, that’s what I’m telling myself.

We’re getting close to Warsaw now and we ease into a suburban station and I see on the platform policemen with dogs on leashes and it’s then I remember the foil of marijuana that is still in the back pocket of my jeans, forgotten. It suddenly feels like a giant conspicuous boulder beneath me, the princess’s pea. I leap up and try to get to the toilet but there’s a line of people wrestling with bags, pushing their way to the door.

I carefully take it out of my pocket and, holding it in the palm of my hand, pretend to rest by holding onto the luggage rack above me. I mould the foil around the chrome bar and when I take my hand away it stays, camouflaged. The people are off now and a policeman is coming on board so I sit back down and open my book. He strides through placing his hands on the headrests either side as he goes. I feel his gaze but don’t look up from the page. He passes and outside on the platform a dog starts barking.

I read the same line over until it makes no sense. “We mix watermelon sugar and trout juice and special herbs all together and in their proper time to make this fine oil that we use to light our world.”

The carriage lurches.

We’re moving again and the last thing I see when we leave the station is a man brushing beads of rain from a women’s coat.